Yom Kippur and the scapegoat

Posted by entheogenic paths on

Tomorrow, here in Israel, we will be "celebrating" a Jewish holiday - a 24-hour fast dedicated, among other things, to the fallen angel Azazel. I dug deeper into the meaning of the name and found that in the Septuagint translation of the Bible (third century BCE), the translator interpreted the word in two different ways.

The first three occurrences of the name Azazel in the chapter are translated using the Greek root "apopomp", meaning "the one who drives away" or "protector from evil." In Greek religion, the expression "hoi ampopompaîoi" refers to divine entities responsible for apotropaic rituals or the recipients of such rituals. These expressions also appear in the context of Greek purification and atonement ceremonies, some of which include the sending away of goats, similar to the biblical ritual and the later, 'kapparot' practice, where a chicken is swung over your head and later beheaded then given to the poor as food, as a symbolic transfer of human impurity accumulated throughout the year. In the final occurrence of the name Azazel, the Septuagint takes a completely different approach. Here, the translator chooses the word "release" or "sending away" (aphesis) of the goat, rather than referring to it by name.

This translation aligns with the etymological connection of Azazel's name to the Aramaic root 'azal, meaning "to go". Thus, the mention of Azazel as a powerful entity disappears entirely from verse 26. Later manuscripts of the Septuagint corrected this early translation to clarify that Azazel referred to a "rugged and fortified place" to which the scapegoat was sent into the wilderness.

According to Enoch 1, the entire world was corrupted by the actions of Azazl (not Azazel), to whom all sins are ascribed. In this text, Azazel is one of the sons of God mentioned in Genesis. He taught humans to make weapons and cosmetics. Because of the revelation of these heavenly secrets, humanity became corrupt and strayed from the righteous path. God ordered Raphael to bind Azazel, cast him into an opening in the desert (Dudael), and cover him with jagged stones and darkness, where he would dwell forever, never to see light again. This story is also found in the Book of Tobit, but there, it applies to Asmodeus.

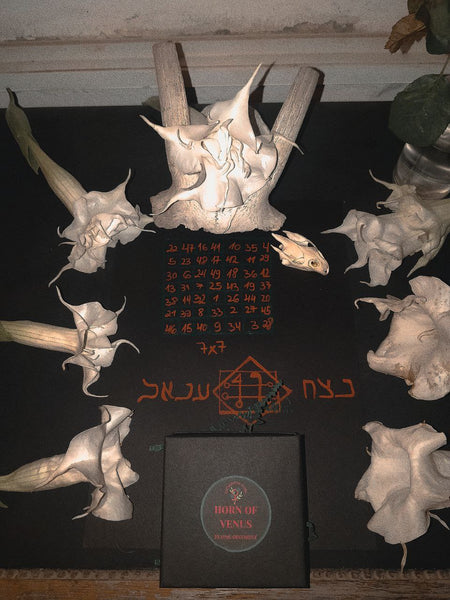

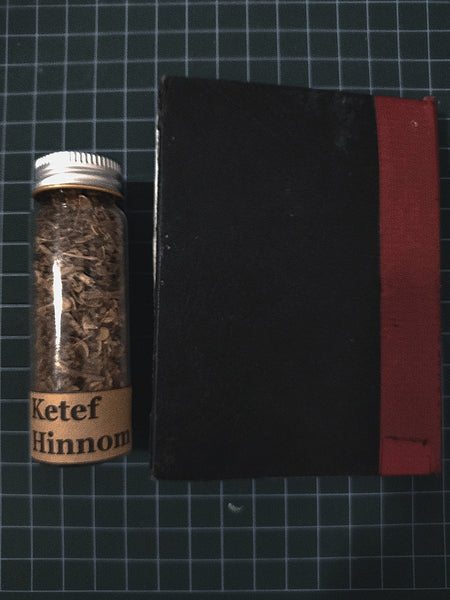

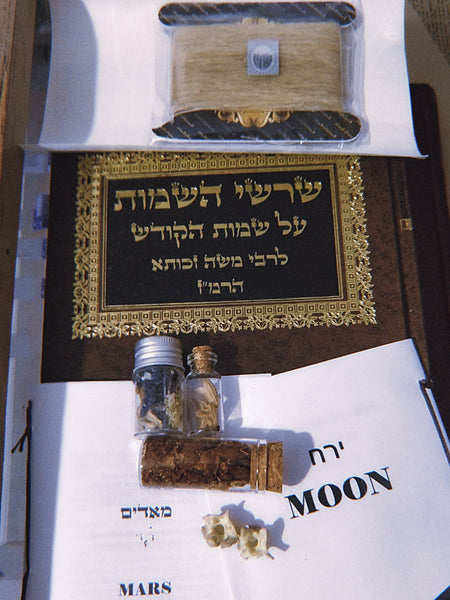

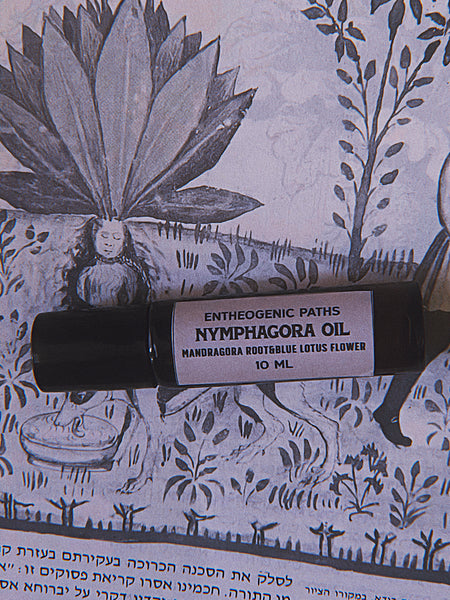

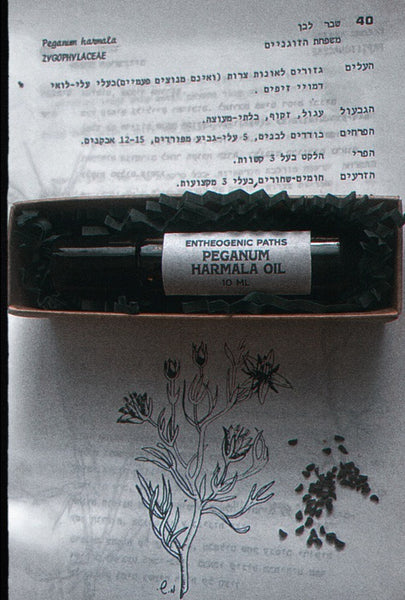

The banishment of Azazel to the desert’s opening in Dudael and the connection to the mandrake root (duda in Hebrew) reflect the deep fears of the demonic forces that humans sought to exploit. Azazel and the poisonous root of the mandrake, which held a special place in magical practices, are both symbols of forbidden knowledge and power that can corrupt. Humans, instead of respecting these secrets, tried to use them for their own benefit. The temptation to draw power from demons and poisons reflects humanity’s desire to control forces they do not fully understand.

In Enoch 3, Azazel is one of three angels - Azza, Uzza, and Azazel - who opposed the elevation of Enoch to the high rank of Metatron.

In modern Hebrew, the word Azazel is used in the curse "go to Azazel", which has a similar meaning to "go to hell". Saying "Azazel" without directing it at someone specific generally reflects frustration or anger.

Azazel also appears in the Quran, in Sura Al-Najm (53:19-20), where the names of three goddesses considered, during the time of Jahiliyyah (society of pre-Islamic Arabia), as daughters of Allah -

Al-Uzza, Al-Lat, and Manat - are mentioned. The worship of these goddesses is also found among the Nabataeans.

Atonement rituals in the ancient Near East are also known from Akkadian literature. The Hebrew root "kapar" is parallel to the Akkadian verb "kuppuru," which is used in Akkadian literature in rituals to appease the gods through purification and the removal of evil. A Babylonian New Year’s ritual describes the purification of Marduk and Nabu’s temples on the fifth day of the festival, using a lamb’s carcass and concluding with the high priest’s prayer at the end of the day.

If only we could send all our troubles to Mount Azazel like the scapegoat, maybe things would look different here. But it seems they're already doing a round in Gaza. This reminds me of George Orwell's saying, "War is peace", because it often feels like problems just find their way back, no matter where we try to send them. In the end, it's always better to face them head-on.

The image of the scapegoat sent out on Yom Kippur is a painting by William Holman Hunt.